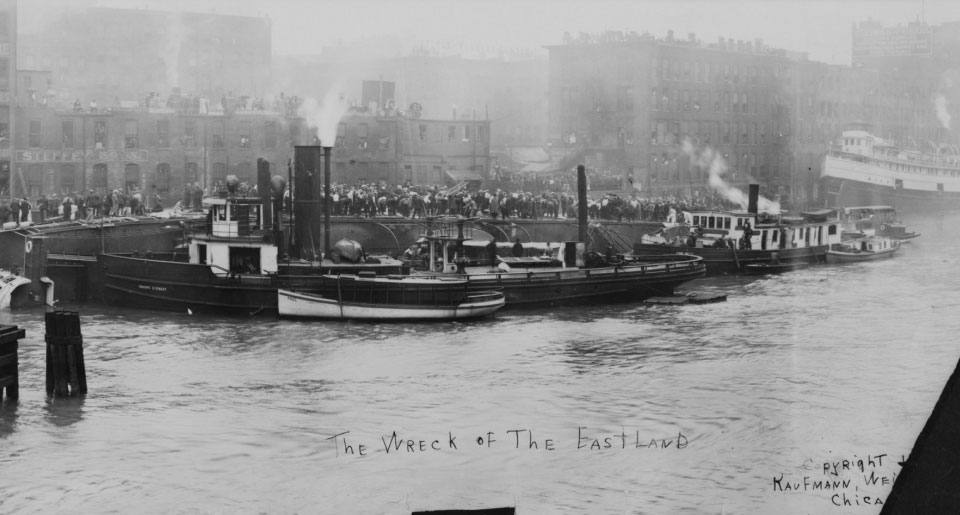

Because the Eastland capsized so suddenly, no lifeboats or rafts were launched. But the crews of other nearby boats and tugs in the area responded quickly, even though there was risk of a boiler explosion on the Eastland.

Earlier that morning, the tug Kenosha had been tied to the bow of the Eastland in preparation for towing it out onto Lake Michigan. Upon watching the Eastland roll into the Chicago River, Captain John O’Meara ordered his tug be secured to the wharf to form a bridge between the overturned hull of the Eastland and the safety of the wharf. Due to the quick and decisive actions taken by O’Meara and his crew, the survival rate of the passengers significantly increased.

Captain Joseph Lamoreaux and his crew of the tug Indiana arrived at the scene and assisted in the rescue and recovery efforts minutes after the Eastland capsized. As a result of his horrifying experience in the rescue and recovery efforts, Captain Lamoreaux had nightmares about the tragedy for several months after the ordeal, and chose not to discuss it with family and friends.

The Theodore Roosevelt, docked immediately to the east of the Eastland (at the southeast corner of the Clark Street bridge) was already boarding passengers for the picnic. It was scheduled to depart shortly after the Eastland. After the Eastland went over, pandemonium broke out on the Roosevelt as women and men screamed and fought to get off the ship and back to safety on shore. Moments later, dozens of victims’ bodies were brought aboard the ship.

Several of the crew and passengers on the Theodore Roosevelt joined in the rescue efforts and threw dozens of life preservers into the river. As soon as Jack James Billow, a 15-year-old deck hand on the Roosevelt, saw the Eastland roll into the river, he and two other deck hands climbed into one of the Roosevelt’s life boats and rowed over to the Eastland. They helped several people into their boat and got them safely to shore before assisting others.

The steamer Petoskey was one of the five ships chartered for the morning excursion and picnic. It had already been boarding passengers when the Eastland rolled over, affording its passengers and crew an unobstructed view of the Disaster. While many stood by and watched, a brave young man named Peter Boyle -- a lookout on the Petoskey -- sacrificed and lost his life by jumping into the river to rescue a woman who had been thrown into the water.

The crew of the Carrie Ryerson was nearby and responded quickly, even though there was risk of a boiler explosion on the Eastland. Ray LeBeau related, “Seven of us piled aboard the tug and we were the first boat there except for the Kenosha. No, I couldn't tell you how many people we got out. The river was full of them and we were too busy to count 'em. I know there were twenty-two people on board the tug at one time. Henry Oderman, one of our shopmen, dived in and got one woman who was going down. It took us a long time to bring her to.”

Three people were down at the Dunham Towing and Wrecking Company plant along the Chicago River: Superintendent F. D. Fredericks, Charlie Hart, and Johnny Benson. Though they didn't have a license and none were a regular engineer, they commandeered the tug Rita McDonald. “Come on boys, I can run that old engine!” Supt. Fredericks shouted to Hart and Benson. According to Fredericks' testimony, it's estimated that they pulled approximately 50 people from the water.

Many other smaller boats that arrived at the scene became floating hearses. As bodies were pulled from the river, they were placed on the decks and covered, later being transported to shore to be transferred to one of the makeshift morgues.