As families walked up and down the aisles trying to identify their loved ones' bodies laid out on the floor of the temporary morgue at the Second Regiment Armory Building, embalmers, undertakers, and funeral professionals were hard at work. As the identification process continued hour after hour and day after day, canvassed sheets were stretched around tables in the corners of the Armory for embalmers to do their work. Most of these professionals had little to no rest for days in the aftermath.

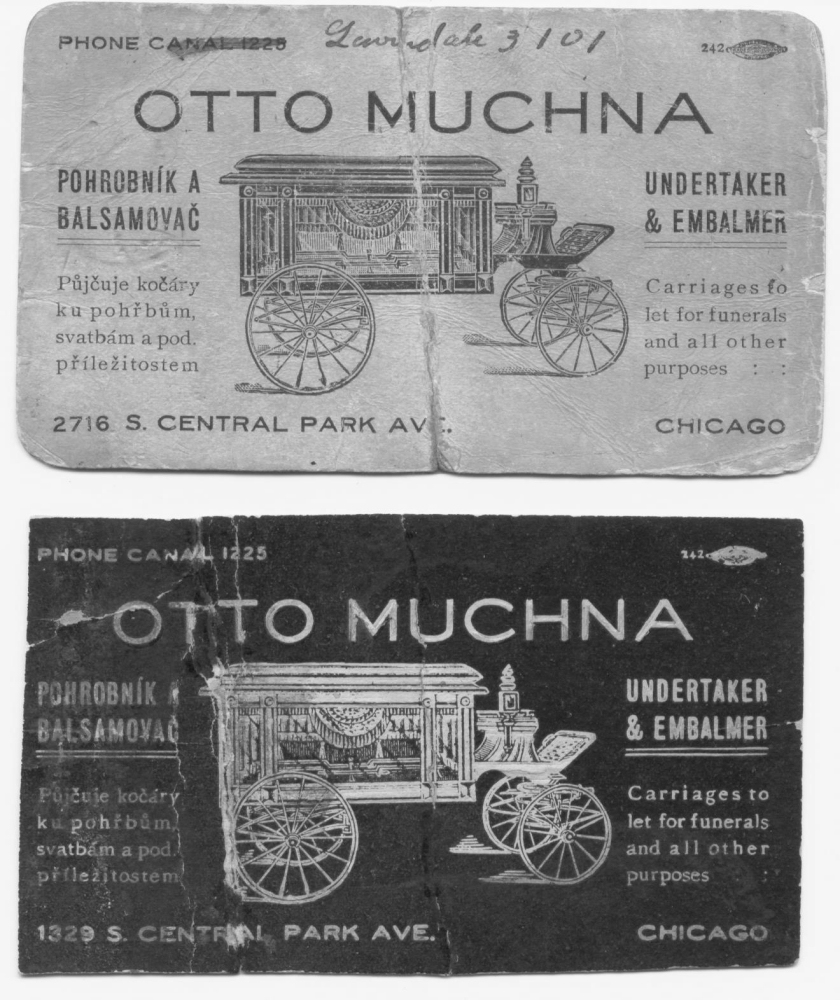

Otto Muchna was one of the many undertakers who worked for days around the clock keeping up with the seemingly endless number of bodies. The Coroner’s records indicate that he performed the services for at least 15 victims. Otto performed the undertaking while his wife, Mary, made the bodies presentable by styling the hair and applying the makeup. The Muchnas’ funeral chapel on South Central Park Avenue did not have enough room for all of the bodies brought there by the horse-drawn carriages. The driveway was enclosed and it, together with the garage, provided additional room. The Muchna's son, Jerry, recalled: "I remember that the poor horses were also worn out because of the many trips to the cemeteries. It took many trips to the Shenandoah Garage to pickup the bodies and then all the trips to the cemeteries which were up to 14 miles away. My dad would return from the cemetery, embalm and prepare another body for burial. It was just too much work for both my dad and my mother, but they did their best."

The owners of Hitzeman Funeral Home recalled: “We took care of 26 bodies, which had to be embalmed and taken to their own homes within two or three days.”

For several days following the tragedy, church bells tolled all day long as funeral processions became a part of many people’s daily routines. Family members, neighbors, and friends carried floral arrangements and wreathes, leading pallbearers through the muddy city streets. One funeral after the other would leave the church. “All that week it was just like tears falling from the sky. It was cloudy and dreary, and the shops were closed down and everyone was mourning,” said survivor Frank Blaha.

Funeral professionals experienced shortages of funeral cars, hearses, and carriages, so trucks were used to take some bodies to the cemetery. Marshall Field & Company loaned 39 of their company auto trucks for the funeral processions. Other firms loaned their company vehicles as well, including the Illinois Athletic Club and Chicago Athletic Club.

The grave digging staff at local cemeteries were overwhelmed. Graves were dug by hand – there were no backhoes – taking two men four hours each to dig a single grave. Nearly 150 graves had to be prepared at Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago alone. Ordinarily, there were four grave diggers on staff at the cemetery. During the week following the Disaster, 52 men were employed, each working more than 12 hours a day.