In less than one hour following the Disaster, John J. O'Connor, Director of the Central Division of the American Red Cross, was at work at the scene of the tragedy. Within a few hours, Ernest P. Bicknell, National Director of the American Red Cross, was speeding on his way from national headquarters in Washington, D. C. to Chicago. At the same time, the Red Cross established a relief station at the Hawthorne Works facility for families of victims who were not Western Electric employees.

Officials of Reid, Murdoch & Company, a wholesale grocery firm, approved the use of their building for the rescue and relief efforts. The building, located directly across the Chicago River from the scene of the accident, was untenanted on July 24, 1915 because Reid, Murdoch & Company employees were attending their annual company picnic. The basement and first floor were opened for the relief efforts. Operators quickly secured the telephone switchboard.

Those who were clinging to life were taken to the first floor for treatment. The deceased were numbered and brought into the large, cement basement where volunteer embalmers were already at work. Police carefully searched the victims' bodies for valuables and identifications, placing all papers and other articles in large envelopes.

Truckloads of stretchers, blankets and other supplies arrived from the State Street department stores offered at no charge. The alley at the rear of the building was congested with scores of trucks and delivery wagons. Each truck was unloaded, then quickly re-loaded with blanket-wrapped bodies and sent to the Second Regiment Armory which had been secured by the Coroner's office as its central morgue.

Shortly after the Coroner's office established the temporary morgue at the Armory, the Red Cross established rest rooms and first aid stations within and saw to the installation of scores of telephones. The Chicago Red Cross nurses chairperson, Miss Minnie F. Aherns, quickly selected a competent staff and provided cots and restoratives for the Armory emergency stations. The emergency stations handled dozens of fainting and hysterical people who entered the temporary morgue. Between midnight and 7 a.m., care is provided for 30 hysterical and exhausted women.

About midday, nurses and physicians were secured to relieve those who were tiring. By afternoon the strain was beginning to show on the rescuers, many of whom had been without food since early morning. Feeding stations were then established on nearby tugs and docks.

On Sunday, the day after the tragedy, the American Red Cross was still hard at work. Company and privately-owned cars are brought to and parked at the emergency relief station. As soon as cases were reported, American Red Cross relief workers left immediately to visit their designated family. Simple instructions were given to the case workers: “Give prompt relief. Ask questions next week.” Depending on the nurse's report information, each relief worker took cash, a physician, interpreter, or whatever else necessary.

The names of 500 families were distributed among nurses, and American Red Cross family worksheet cards were also given. They opened an emergency relief station at the Western Electric Company Hawthorne facility where the needs of each family was identified. The families were grouped into three categories:

- Those needing immediate assistance, mainly in connection with funerals

- Those needing assistance after the burials

- Those needing possible future assistance

Hours after the Eastland rolled onto its side, the victims’ families looked to the courts for appropriate compensation from those to be held accountable for the deaths. To help determine who should be held accountable, Cook County Coroner Peter M. Hoffman convened a jury in mere hours.

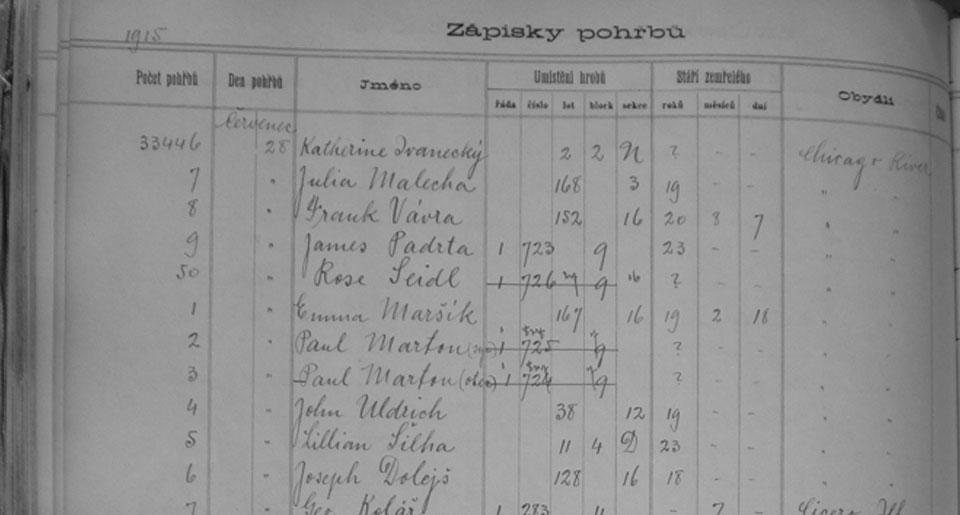

Although the Coroner’s official cause of death of the victims was “drowned,” it was apparent that many people struggled after being thrust into a fight for their lives. As the number of bodies grew and before the situation got out of control, Coroner Peter Hoffman procured the use of the Second Regiment Armory to serve as the central morgue. The Armory was located nearly 1.5 miles west of the Disaster scene on Washington Boulevard at Curtis Street. Bodies were continually brought to the central morgue throughout the day and in the days that followed. As fast as bodies were brought up out of the river, they were brought to the central morgue.

The doors to the Armory opened around midnight. The tiniest victims of the tragedy – infants and young children – were placed together in a separate section. The families endured the never-ending procession of hunting for their spouse, one or more of their children, entire families in some cases. Many described the scene inside the Armory as horrifying. “I saw hundreds of dead laid in rows,” said Harlow Eldredge Smoot. “Mothers still holding their babies. Women with handfuls of other women’s hair! And the agony expressed on the faces of the dead. Young people dressed in white dresses and trousers, and after being thrown into that stinky, dirty water of the Chicago River they looked awful. I shall never forget [it].”

The Coronor's Office awarded and honored many brave citizens who assisted them in the aftermath with a star inscribed "Valued Services Rendered." A letter was also given to these individuals. One letter from the Coroner read, in part: "I trust that you will accept this little token not for its intrinsic value or worth, but in memory of this terrible of all disasters which should teach us the lesson of 'Safety First' and of extending to our fellowman kindness, courtesy and consideration."