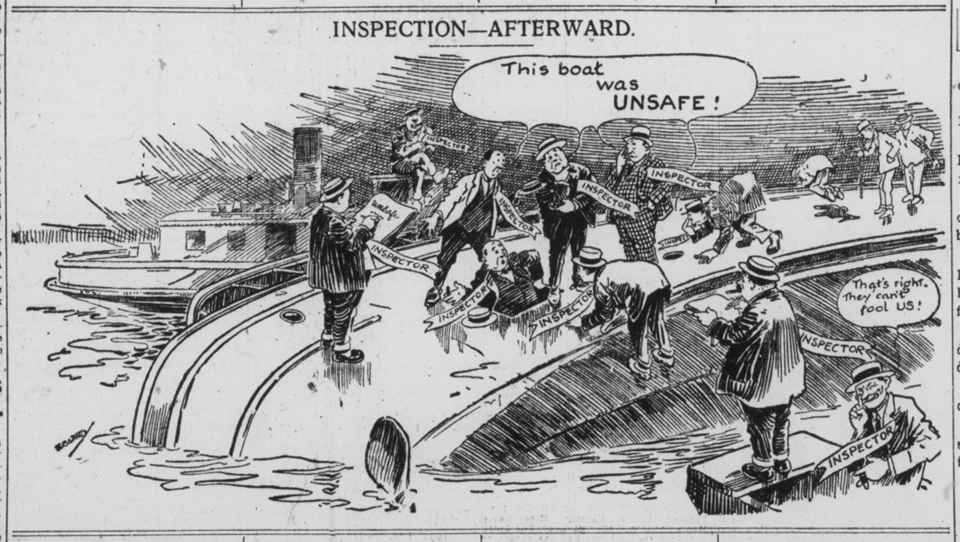

Immediately following the Eastland Disaster, the public rightly demanded that the causes be determined and that someone be held accountable.

In response to the public pressure to hold someone accountable, seven separate inquiries were started to investigate the criminal actions.

The Cook County Coroner’s Office acted first and immediately began its investigations. Coroner Peter M. Hoffman convened a jury hours after the Eastland rolled onto its side.

Two days after the Coroner’s jury issued its recommendation, however, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, to whose district court the federal case had been assigned, issued an injunction prohibiting anyone from appearing before any hearing other than his own.

The Illinois grand jury examined the charges submitted by the Coroner’s jury and subsequently brought forth several indictments.

Amonth later, State’s Attorney Maclay Hoyne agreed to allow the federal action to be disposed of before any state action was taken. This sealed the fate of any state justice being done as no criminal prosecution was pursued and the charges were subsequently dropped five years later.

Federal actions were initiated on July 24 when President Woodrow Wilson wired Secretary of Commerce William Redfield and instructed him to travel to Chicago to initiate a Federal inquiry. Redfield began his inquiry when he arrived in Chicago on July 29. The proceedings continued through July 31.

Just as with the Coroner’s inquiry, this inquiry was truncated by the Judge Landis injunction prohibiting anyone from appearing before any other hearing.

The Federal grand jury began its hearings on July 30. It heard over 100 witnesses.

Two months later the Federal grand jury brought indictments against

the ship’s owners, the leasing company, the captain and chief engineer, the government inspectors, the St. Joseph-Chicago Steamship Company, and the Indiana Transportation Company. The indictments included conspiracy to defraud the federal government by preventing the execution of marine laws, and criminal carelessness.

Several days later, a bench warrant was issued by Judge Landis for the arrest of all but the government inspectors. (These men were residents of Michigan.) The original charges – conspiracy to defraud the federal government by preventing the execution of marine laws, and criminal carelessness – were changed to a single charge of conspiracy to operate an unsafe ship.

The case was assigned to Judge Clarence Sessions of the District Court of Grand Rapids, Michigan. The prosecution was carried on by U.S. District Attorney Charles Clyne.

The defendants had individual attorneys, notably James Barbour, who represented the captain, and Clarence Darrow, who represented the chief engineer.

In February 1916, Judge Sessions delivered his decision: The defendants were found not guilty. This was the only possible outcome as there was no probable cause that a conspiracy took place. The District Court also denied the extradition of the defendants from Michigan to Illinois, thus concluding the Federal criminal actions which meant that no criminal trial was ever held in Chicago.

Sessions did not make any judgment about the seaworthiness of the

Eastland, an issue that would loom large in the civil case.